Researchers at NUST MISIS have discovered the most effective method of processing an aluminum alloy, which allows the material to become three times stronger while maintaining optimal hardness and ductility. In the future, this approach could enable manufacturers to eliminate costly alloying additives, producing lightweight and durable components for microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) that retain their properties through multiple work cycles.

Aluminum alloys in the 5xxx series are versatile materials known for their strength, corrosion resistance, and light weight. These alloys are used in the production of fuel tanks and aircraft fuselages, automotive panels and frames, ship hulls and deck equipment, as well as sensors and wires in microelectronics. In construction, they are used for windows, facades, and stained glass, while in the food and chemical industries, they serve in technological equipment. However, further enhancement of such materials is limited, as traditional methods are energy-intensive and require expensive alloying elements.

Evgenia Naumova, a candidate of technical sciences and associate professor at the Department of Pressure Metalworking at MISIS, shared: “Microelectronics companies do not need to create new alloys or reconfigure their production lines. The proposed approach is technologically simpler and cheaper than traditional hardening methods. It will also extend the lifespan of products, which in the long run will reduce maintenance and replacement costs.”

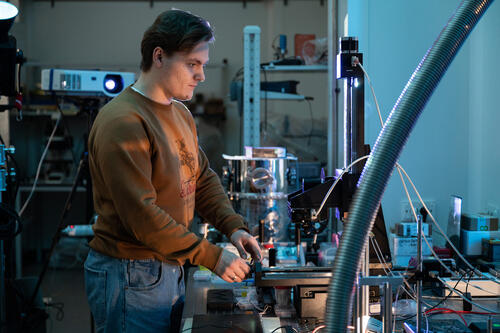

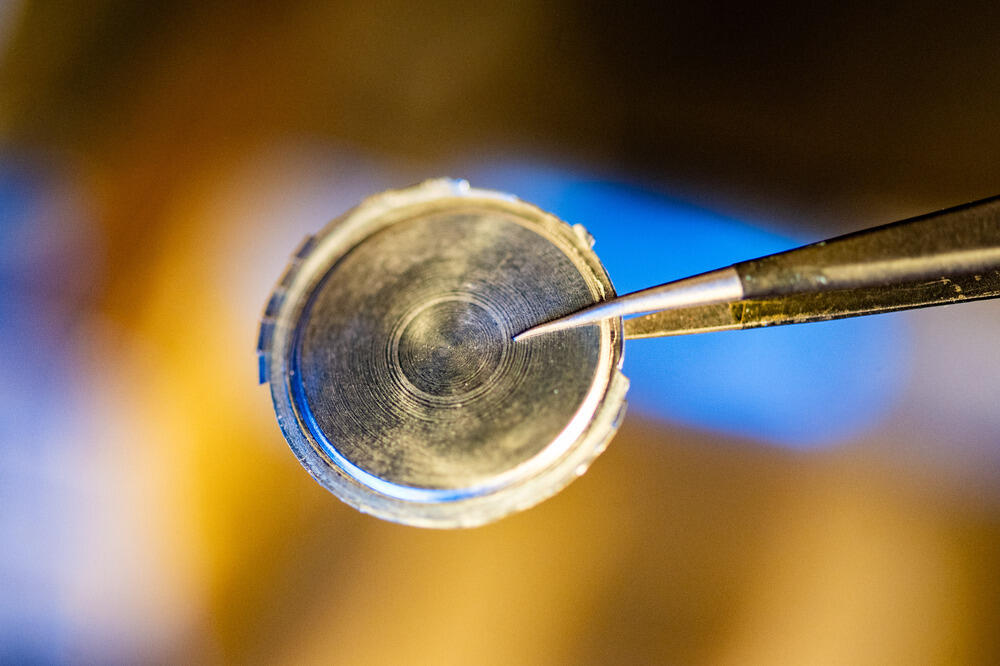

The high-pressure twisting method is one of the most effective ways to strengthen metals without altering their chemical composition. During the process, the sample is placed between sturdy anvils and twisted under pressure of tens of thousands of atmospheres. Under these conditions, the material’s structure becomes nanocrystalline, giving the alloy a unique combination of strength and ductility.

“Intensive deformation changes the internal structure of the aluminum alloy: large grains are transformed into ultra-fine ones, which leads to a sharp increase in strength without sacrificing ductility. Given the compact size of the workpiece, we see the primary potential of this material in microelectromechanical systems, where lightweight, durable structures—such as sensors and actuators—are required to maintain their properties through multiple work cycles and resist high temperatures,” Stanislav Rogachev, Doctor of Technical Sciences and associate professor at the Department of Metallography and Strength Physics at MISIS.

The detailed results have been published in the scientific journal Russian Metallurgy (Metally). The research was supported by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (No. 20-19-00746-P).